Belgian scientists turn polluted air into hydrogen fuel

May 16, 2017 | Tuesday | News

Researchers in Belgium are developing a device that cleans up the air and generates power at the same time.

Image Source: KU Leuven News

Scientists from the University of Antwerp and KU Leuven (University of Leuven) in Belgium are developing a device that cleans up the air and generates power at the same time. It relies on a process called 'heterogeneous photocatalysis,' which has been used previously to siphon hydrogen from water and nullify gas-based pollutants. However, it's rarely been used to do both at once, but the team now appears to have managed it thanks to what's called a "photoelectrochemical cell," which makes use of solar cells to produce hydrogen in a similar way to electrolysis water-splitting.

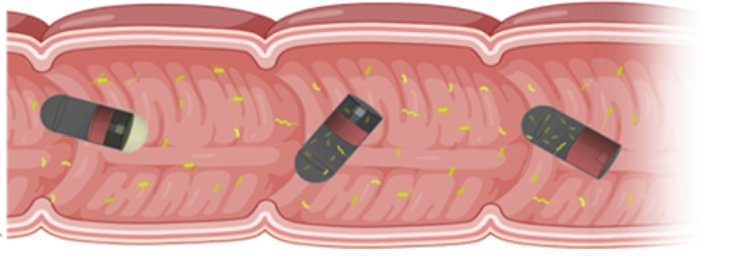

“We use a small device with two rooms separated by a membrane,” explains Professor Sammy Verbruggen (UAntwerp/KU Leuven). “Air is purified on one side, while on the other side hydrogen gas is produced from a part of the degradation products. This hydrogen gas can be stored and used later as fuel, as is already being done in some hydrogen buses, for example."

In this way, the researchers respond to two major social needs: clean air and alternative energy production. The heart of the solution lies at the membrane level, where the researchers use specific nanomaterials. “These catalysts are capable of producing hydrogen gas and breaking down air pollution,” explains Professor Verbruggen. “In the past, these cells were mostly used to extract hydrogen from water. We have now discovered that this is also possible, and even more efficient, with polluted air.”

It seems to be a complex process, but it is not: the device must only be exposed to light. The researchers’ goal is to be able to use sunlight, as the processes underlying the technology are similar to those found in solar panels. The difference here is that electricity is not generated directly, but rather that air is purified while the generated power is stored as hydrogen gas.

“We are currently working on a scale of only a few square centimetres. At a later stage, we would like to scale up our technology to make the process industrially applicable. We are also working on improving our materials so we can use sunlight more efficiently to trigger the reactions. "

Source: KU Leuven